The pursuit of knowledge, particularly concerning the intricate tapestry of human civilization, has always been a primary directive in my personal and professional endeavors. Consequently, when the opportunity arose to embark upon an expedition to Hubei, a province renowned for its Hubei historical treasures, it was an undertaking I approached with rigorous analytical planning. My objective was not merely to observe, but to delineate the underlying architectural, cultural, and societal paradigms that have shaped this region for millennia. This 7-day itinerary, meticulously structured to optimize the exploration of Hubei historical treasures, proved to be an illuminating journey, challenging certain preconceived notions and reaffirming others, in a manner characteristic of cognitive confirmation bias when presented with new data. The experience was a profound cultural heritage exploration, offering insights into ancient Chinese dynasties that are often overlooked in broader narratives.

It is imperative to underscore that for an individual accustomed to the structured logic of software architecture and the precision of data analysis, the immersion into historical landscapes presents a unique set of challenges and rewards. The initial anticipation, perhaps influenced by an echo chamber of Western media representations, was a somewhat monolithic view of ancient Chinese dynasties. However, the empirical data gathered during this extensive cultural heritage exploration in Hubei decisively recalibrated this perspective. The sheer diversity of the Hubei historical treasures observed, ranging from imperial tombs to ancient city roots, necessitated a re-evaluation of prior assumptions, affirming the rich, multi-faceted nature of China’s past.

For those contemplating a similar venture, especially from North America, Europe, or Australia, it is essential to prepare for a distinct cultural milieu. Navigating China necessitates certain digital tools. For instance, a reliable mapping application such as Amap – China’s leading mobile map application is indispensable for accurate navigation, particularly within the labyrinthine streets of older cities. Furthermore, for seamless communication and mobile payments, WeChat – China’s ubiquitous messaging and payment app is a fundamental requirement. The logistical efficacy of one’s journey is significantly enhanced by these technological leverages.

Day 1-2: Zhongxiang and the Enigmatic Ming Xianling Mausoleum – Unveiling Hubei Historical Treasures

My journey commenced in Zhongxiang, a city that harbors one of the most intriguing Hubei historical treasures: the Ming Xianling Mausoleum. This UNESCO World Heritage site, spanning an impressive 183.13 hectares, is a testament to the architectural prowess and intricate geomantic principles of the Ming Dynasty. Constructed over 47 years, beginning in 1519, it serves as the joint tomb of Emperor Jiajing’s parents, Prince Zhu Youyuan and Empress Jiang. The initial perception, shaped by academic texts, was of a grand, yet conventional, imperial resting place. However, the reality presented a paradigm shift in understanding the complexities of dynastic power and filial piety.

The “One Mausoleum, Two Mounds” Anomaly

The most striking feature, and indeed a focal point for any cultural heritage exploration, is the “one mausoleum, two mounds” structure. This unique dumbbell-shaped layout, where two treasure cities (baocheng) are connected by a ‘yaotai’ or elevated platform, is unparalleled among Chinese imperial tombs. It stands as a palpable artifact of the ‘Great Rites Controversy’ – a significant political struggle during Emperor Jiajing’s reign to elevate his birth parents’ status. My analytical mind immediately sought to understand the socio-political undercurrents that necessitated such a deviation from established imperial protocols. It is a robust solution to a very complex problem of legitimacy and lineage. The sheer audacity of this architectural statement, defying centuries of tradition, underscores the formidable will of Emperor Jiajing.

Architectural Grandeur and Geomantic Principles

- Golden Vase Outer Wall (Jinping Luocheng): From an aerial perspective, the outer wall forms a colossal ‘vase’ shape, undulating with the terrain. This is another singular feature among Ming imperial tombs. The engineering required to achieve this organic yet precise form, harmonizing with the natural landscape, is profoundly impressive.

- Nine-Bend Imperial River (Jiuqu Yuhe): An S-shaped river meanders through the complex, segmenting the grounds and skillfully leveraging the natural topography of mountains, water, and trees. This design not only serves aesthetic purposes but also adheres to sophisticated Feng Shui principles, ensuring prosperity and tranquility. It is a testament to ancient environmental engineering.

- Dragon-Shaped Spirit Way (Longxing Shendao): Unlike the typical straight imperial avenues, this spirit way intentionally curves, preventing an immediate panoramic view of the mausoleum. This “winding path leading to a secluded spot” effect creates a sense of anticipation and reverence, aligning with traditional Chinese aesthetics and geomancy. The deliberate avoidance of linearity here is a fascinating counterpoint to modern architectural efficiency, yet its efficacy in evoking emotion is undeniable.

- Qionghua Double Dragon Glazed Screen Wall (Qionghua Shuanglong Liuli Yingbi): Located beside the Ling’en Gate, these vibrant glazed screen walls feature intricate Qionghua flower patterns on the front and two dragons playing with a pearl on the reverse. The craftsmanship represents the zenith of Ming Dynasty glazed tile artistry. The vivid colors and detailed mythical creatures provided a stunning visual contrast to the more somber, monumental stone structures, reminding one of the artistic flourishes within robust solutions.

The entire layout, particularly the “double dragon playing with a pearl” geomantic formation, with the winding spirit way as one dragon, the nine-bend imperial river as another, and the inner Mingtang pond as the pearl, demonstrates an unparalleled mastery of Feng Shui. It is a comprehensive system designed to harness natural energies for imperial blessing and longevity. One might infer that such elaborate designs were not merely superstitious but represented a sophisticated understanding of land use and symbolic representation, deeply embedded in the ancient Chinese dynasties’ worldview. The cost of such an endeavor, both in resources and human labor, must have been astronomical, underscoring the immense power wielded by the imperial court.

Admission to Ming Xianling is 60 RMB. For individuals with the surnames Zhu or Jiang, entry is complimentary upon presentation of identification, a rather quaint and specific perk. The journey from Jingmen city center takes approximately 40 minutes by car. The site is open from 8:30 to 17:30, with last entry at 17:00. This particular Hubei historical treasures site provides a tangible link to the imperial past, offering a rich cultural heritage exploration for those interested in the intricate details of ancient Chinese dynasties.

Day 3: Shennongjia and the Ancestral Shennong Altar – A Spiritual Cultural Heritage Exploration

The third day led me to Shennongjia, a region of profound natural beauty and spiritual significance, home to the Shennong Altar. This location, deeply intertwined with the legend of Emperor Yan, Shennong, the divine farmer, is another crucial element in understanding Hubei historical treasures. Shennong is revered as the progenitor of agriculture and traditional Chinese medicine, having tasted countless herbs to discover their properties. Standing before the colossal statue of Shennong, one cannot help but feel a profound sense of connection to the origins of Chinese civilization. It is a moment where the analytical mind pauses, giving way to a more visceral, almost ancestral, recognition. This sacred site offers a unique cultural heritage exploration into the foundational myths of ancient Chinese dynasties.

The Shennong Statue and Sacrificial Altars

The monumental statue of Emperor Yan Shennong is undeniably the centerpiece. The 243 stone steps leading up to it are divided into ‘civilian’ and ‘official’ paths, a subtle yet profound delineation of social hierarchy even in sacred spaces. The five altars, symbolizing the ‘nine-five尊’ (a metaphor for the emperor’s supreme status), reflect ancient cosmic beliefs. The ground altar, paved with cobblestones, symbolizes peace, with its inner five circles representing the Five Elements and the outer square within a circle embodying the ancient wisdom of ‘heaven is round, earth is square’. As a software architect, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to structured data and modular design; the entire setup is a meticulously designed system for spiritual interaction, a robust solution for a spiritual paradigm. It is an extraordinary cultural heritage exploration.

- Ritualistic Practices: Visitors are encouraged to ascend via the right (civilian) path and descend via the left (official) path. Standing in the center of the ground altar, which represents ‘earth’ in the Five Elements, is believed to foster growth. On the left side of the statue, one can strike a bell three times for blessings; on the right, beat a drum nine times. These rituals, though seemingly simple, are deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of ancient Chinese dynasties, providing a tangible connection to historical spiritual practices.

- Inner Sanctum Etiquette: Inside the temple, where consecrated bronze statues of Shennong reside, strict etiquette is observed: no photography, hats off, sunglasses removed, and appropriate attire. One must enter with the left foot first, avoiding stepping on the threshold. These rules underscore the sanctity of the space and the reverence for Shennong, a crucial aspect of understanding Hubei historical treasures in their spiritual context.

The Millennium Fir King (Qiannian Shanwang)

Beyond the altars, the Millennium Fir King, a 1300-year-old fir tree, stands as a living testament to history. Towering at 48 meters, its trunk requires six people to embrace. This tree has witnessed the ebb and flow of dynasties – Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing – a silent guardian of the land. It epitomizes the concept of enduring natural heritage alongside the constructed Hubei historical treasures. The local custom of walking clockwise around the tree (three times for those whose zodiac sign clashes with the year’s earthly branch, once for others) for blessings is a fascinating blend of animism and traditional cosmology. It is a poignant reminder that even within the most analytical frameworks, there exists a human need for connection to the ancient and the mystical. This further enriches the cultural heritage exploration.

The journey to Shennongjia, particularly the Shennong Altar, typically requires approximately 1.5 hours for exploration. Access is primarily by self-drive to Muyu Town. The transformation of the Shennong Altar area, as observed from recent comparisons, has sparked debate. While some lament the loss of the “primitive mystery” of the moss-covered, off-white structures, preferring the aesthetic that evoked “infinite longing for our Chinese ancestors,” the current, more vibrant aesthetic, reminiscent of a “Patrick Star” hue, caters to a different contemporary sensibility. This divergence in aesthetic preference highlights an interesting aspect of cultural preservation versus modernization, a dichotomy that often arises when engaging with Hubei historical treasures.

Day 4: Wuhan – The Heart of Hubei’s Ancient and Modern Echoes

Wuhan, a sprawling metropolis, serves as a crucial nexus for understanding the historical trajectory of Hubei. My fourth day was dedicated to exploring its diverse offerings, from ancient tombs to significant cultural institutions. The city itself is a microcosm of China’s urban evolution, having transitioned through four distinct phases from pre-Qin “yi-system” cities to modern metropolises. This layered history presents a robust dataset for any cultural heritage exploration. The Hubei historical treasures found here are particularly diverse, reflecting centuries of strategic importance and cultural synthesis.

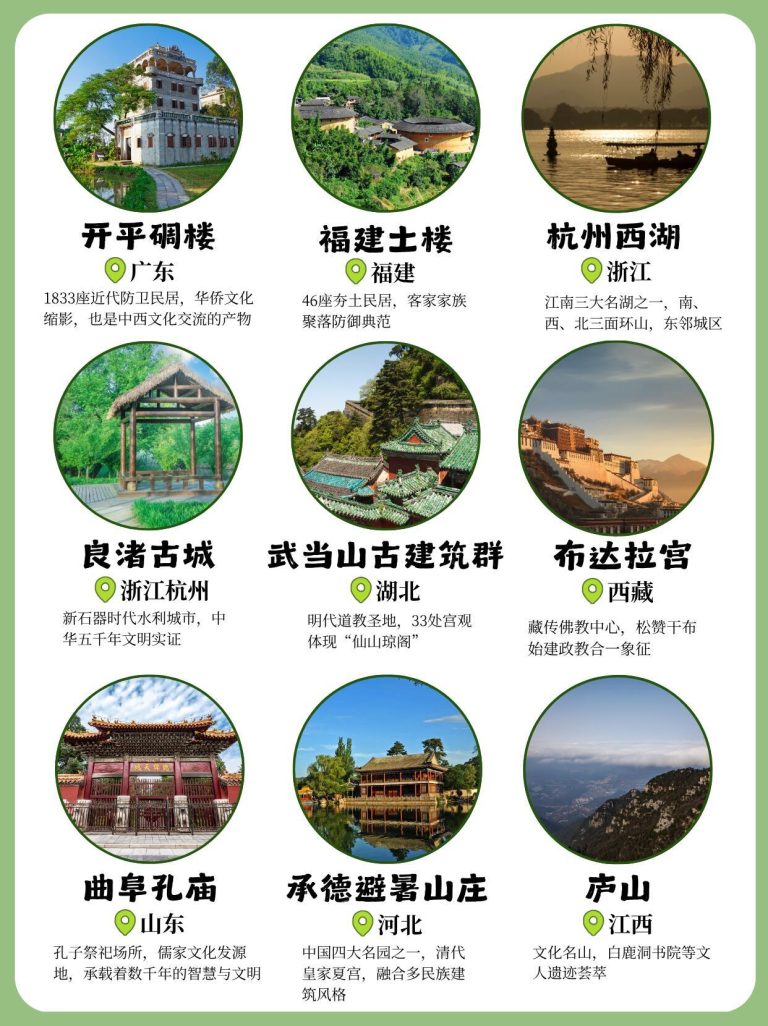

Hubei Provincial Museum – A Repository of Ancient Chinese Dynasties

The Hubei Provincial Museum is an indispensable stop for anyone interested in ancient Chinese dynasties and the rich cultural heritage exploration of the region. It is not merely a collection of artifacts but a comprehensive narrative of Jingchu civilization. I allocated half a day, a timeframe that proved barely sufficient to absorb the sheer volume of information. The museum, free to enter with prior reservation, is open from 9:00 to 17:00 (closed Mondays) and is conveniently accessible via Metro Line 8 to “Provincial Museum Hubei Daily Station.”

- Zenghouyi Bianzhong (Marquis Yi of Zeng’s Bronze Bells): This bronze chime set, the largest and best-preserved ever unearthed, represents the pinnacle of pre-Qin ritual music. Its intricate design and precise tuning capabilities are a marvel of ancient acoustic engineering. It fundamentally rewrites our understanding of ancient musical history, a true Hubei historical treasures.

- Sword of Goujian, King of Yue: This legendary sword, famous for remaining rust-free and razor-sharp after millennia, is a testament to extraordinary bronze casting techniques of the Spring and Autumn period. Its exquisite patterns and enduring quality present a fascinating case study in ancient metallurgy.

- Zenghouyi Zunpan (Marquis Yi of Zeng’s Bronze Zun and Pan): A pair of bronze ritual vessels, featuring intricate openwork decoration and dozens of components, showcasing the supreme level of ancient casting technology. The complexity of its assembly and aesthetic refinement are truly breathtaking.

- Tiger-Seat Bird-Frame Drum (Huzuo Niaojiagu): This iconic Chu culture totem, with two tigers forming the base and two phoenixes soaring upwards, embodies the romantic imagination of the Chu people. Its appearance on national television broadcasts underscores its cultural significance.

- Painted Figures and Chariots on Lacquer (Caihui Renwu Chema Chuxingtu): This “comic strip” of lacquer painting depicts figures, chariots, animals, and trees in a coherent, dynamic narrative. It is an early example of sequential art, offering insights into daily life and artistic conventions of the time.

- Yuan Blue and White Porcelain Plum Vase with “Four Loves” (Yuan Qinghua Si’aitu Meiping): A rare masterpiece of blue and white porcelain, depicting the “Four Loves” motif. Its vivid figures and artistic execution have earned it the moniker “Panda of Ceramics.”

- Shuibudi Qin Bamboo Slips (Yunmeng Shuihudi Qinjian): These “underground archives” systematically record the legal system of the Qin Dynasty, providing invaluable primary source material for historical and legal studies. It is a robust dataset for understanding ancient governance.

- Yunxian Man Skull Fossil (Yunxian Ren Tougu Huashi): The first ancient human skull fossil discovered in Hubei, crucial for understanding human evolution in East Asia. This tangible evidence provides a direct link to our prehistoric ancestors.

- Shijiahe Jade Figures (Shijiahe Yurenxiang): Outstanding examples of prehistoric jade carving, with realistic forms and delicate craftsmanship, demonstrating the mature development of jade artistry in the late Neolithic period.

- Chongyang Bronze Drum (Chongyang Tonggu): One of the earliest extant bronze drums, complete with body, seat, and crown. It is a vital artifact for studying ancient musical instruments and ceremonial practices.

The museum’s collection undeniably reinforces the grandeur of ancient Chinese dynasties, particularly the Chu state, which once held its capital in Jingzhou. The sheer volume and quality of these Hubei historical treasures are astounding for a provincial institution, challenging any prior confirmation bias that national museums exclusively house such paramount artifacts. This visit was an intensive cultural heritage exploration, requiring focused attention to fully appreciate the intricacies of each exhibit. The layout, while extensive, is logically structured, allowing for a systematic traversal of historical periods.

Ming Chu King’s Tombs – Royal Necropolis and Ancient Trees

Later, I ventured to the Longquan Mountain in Jiangxia District to explore the Ming Chu King’s Tombs. This site, often referred to as “Thirteen Ming Tombs in the North, Nine Royal Tombs in the South,” is a testament to the regional power of the Ming imperial family. Prince Zhu Zhen, the sixth son of Emperor Hongwu, established his fiefdom in Wuchang in 1381. He selected Longquan Mountain as his final resting place, a choice that led to the construction of a sprawling necropolis mirroring the imperial tombs near Beijing. This extensive complex, covering approximately 7.6 square kilometers, houses the tombs of nine Chu kings across eight generations.

The layout of the tombs adheres to strict hierarchical principles, with Prince Zhu Zhen’s Zhaoyuan at the center, facing south with Tianma Peak as its backing. The other eight royal tombs are arranged symmetrically on Yuping Peak, guarding Zhaoyuan. This organizational schema is a clear manifestation of the Ming Dynasty’s rigorous social and political structures, offering another lens through which to view ancient Chinese dynasties. The sheer scale of these Hubei historical treasures is difficult to fully comprehend without direct observation. It is a powerful example of scalable architecture for the deceased.

A notable feature within the scenic area is the “Granny Tree” (Popo Shu), a 700-year-old Coral Hackberry, the oldest tree in Optics Valley. Its gnarled roots, resembling dragons, are locally interpreted as “Nine Dragons Attending a Gathering,” symbolizing the nine Chu kings interred there. This organic sculpture offers a fascinating intersection of nature, history, and folklore. The synergy between natural phenomena and human interpretative frameworks is a recurring theme in Chinese cultural heritage exploration. The logistical challenge of reaching this site, involving a metro ride to Fozuling Station and then a taxi, underscores the importance of planning for optimal travel efficacy.

Hanyang Gongyuan Historical Exhibition Hall – The Cradle of Imperial Examinations

My exploration of Wuhan continued with a visit to the Hanyang Gongyuan Historical Exhibition Hall, which opened to the public on October 1, 2025. Located on the second floor of the former St. Columban’s Hospital, this exhibit systematically presents the imperial examination system, educational culture, and urban heritage of the Hanyang region during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The Hanyang Gongyuan, originally established in the Ming Dynasty, served as the examination hall for scholars taking provincial and metropolitan examinations. The area was historically rich in educational institutions, including Wenchang Palace and Qingchuan Academy, fostering a profound scholarly atmosphere. This site provides a robust insight into the meritocratic yet often flawed system that shaped ancient Chinese dynasties.

The “Gongmian Street Archway,” originally the Gongyuan Archway, a six-pillar, five-gate stone structure, stands as one of Wuhan’s oldest surviving archways, designated an outstanding historical building in 1993. The exhibition utilizes various media—graphics, models, and scene recreations—to illustrate the architectural layout of the Gongyuan, the examination process, and the illustrious list of Hanyang’s successful scholars. It also traces the 300-year educational legacy from Qingchuan Academy to Wuhan No. 3 High School, highlighting Hanyang’s historical significance in both civil and martial arts. This specific Hubei historical treasures site offers a glimpse into the intellectual infrastructure that supported ancient Chinese dynasties.

Admission is free, with no prior reservation required, though crowd control may be implemented during holidays. The exhibition is open from 9:00 to 17:00, closed on Mondays. It is conveniently located near Lanjiang Road Metro Station (Line 4, Exit B). I recommend visiting the Hanyang Tree Science Popularization Museum on the first floor before ascending to the Gongyuan exhibition, then taking a short walk to the outdoor Gongmian Street Archway to complete the “Hanyang Cultural Pulse Golden Hundred Meters” circuit. This methodical approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of this specific cultural heritage exploration.

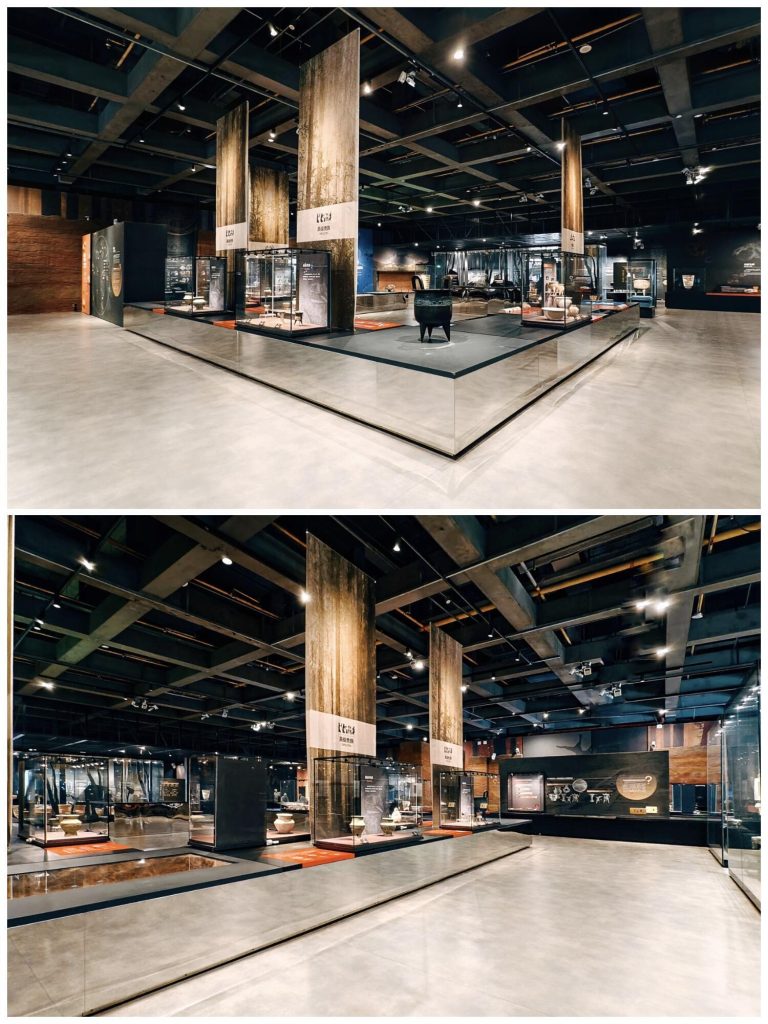

Panlongcheng Ruins Museum – The Root of Wuhan City

My final stop in Wuhan was the Panlongcheng Ruins Museum, situated in the Hankou suburbs. Dating back approximately 3500 years, Panlongcheng is a high-level city site from the early Shang Dynasty in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. It is widely regarded as the “root of Wuhan city.” Discovered in 1954 and excavated since 1963, it was designated a National Archaeological Site Park in 2017 and officially opened in 2019. This site represents a foundational layer of Hubei historical treasures.

The excavations at Panlongcheng have revealed palace city sites, tombs, bronze casting workshops, and a wealth of artifacts including stone tools, pottery, bronze vessels, jade, and turquoise. While some of the most exquisite bronze pieces are housed in the Hubei Provincial Museum, the overall exhibition at Panlongcheng is exceptionally well-curated. The spacious halls provide ample room for display and comprehensive explanations of the artifacts’ functions. The design of the exhibition panels is particularly commendable, contributing to the museum’s recognition with a “Top Ten Exhibition Fine Arts Award” in 2020. This museum offers a deep dive into the early stages of ancient Chinese dynasties’ urban development and material culture, a truly compelling cultural heritage exploration.

The museum’s reputation for its special exhibitions, such as the “Treasures of Ancient Civilizations in the Yangtze River Basin” that I was fortunate to witness, further solidifies its standing. The serene environment, coupled with the proximity to Mulan Lake, makes it an ideal location for an immersive historical experience, though visitors should plan to bring their own provisions as commercial facilities are minimal. The efficacy of a well-designed exhibition in conveying complex historical narratives is evident here. This site unequivocally demonstrates the profound legacy of Hubei historical treasures.

Day 5: Jingzhou – A Strategic Citadel of the Three Kingdoms and Chu Culture

Jingzhou, a city steeped in 3000 years of history, served as the capital of the Chu State for over 500 years and was a pivotal strategic point during the Three Kingdoms period. My fifth day was dedicated to a comprehensive cultural heritage exploration of this ancient city, which holds an abundance of Hubei historical treasures. The city’s dual identity, as both a cradle of Chu culture and a battleground for legendary figures like Guan Yu, provides a rich, albeit complex, historical narrative.

Jingzhou Ancient City Wall – A Fortified Bastion

The Jingzhou Ancient City Wall, one of the best-preserved ancient city walls in China, is a magnificent structure of Ming and Qing brickwork, encircling the city with a moat. Its circumference of 10,000 meters and six active gates offer a tangible connection to the past. Walking atop the wall, overlooking the vast plains, one can almost visualize the strategic importance of “Guan Yu defending Jingzhou.” The lush greenery and the surrounding moat create a remarkably pleasant environment for exploration. However, the relative lack of bustling commercial activity within the walls, a stark contrast to other walled cities I have visited, was a point of observation. This might be perceived as a slight operational inefficiency from a modern tourism perspective, yet it undeniably preserves a certain historical tranquility. It is a monumental Hubei historical treasures site.

Jingzhou Museum – A Treasure Trove of Chu and Han Artifacts

The Jingzhou Museum, a free institution, houses an astonishing collection of national treasures, including Warring States and Han Dynasty lacquerware, Chu jade artifacts, the Sword of Fuchai, the Sword of Goujian, and remarkably, a well-preserved Western Han wet corpse known as “Old Comrade Sui.” The sheer quality and historical significance of these exhibits are exceptional for a municipal museum, rivaling those of some provincial institutions. The museum’s collection of Chu artifacts is particularly noteworthy, given Jingzhou’s past as the Chu capital. The distinct, sometimes “exotic and eerie” aesthetic of Chu culture, diverging significantly from the more rectilinear aesthetics of the Central Plains, provides a fascinating subject for cultural heritage exploration. This unique stylistic divergence, which I had previously encountered in academic literature, was powerfully confirmed by the direct observation of the artifacts. It is a profound collection of Hubei historical treasures.

The presence of multiple Swords of Goujian, including the one found in Jingzhou, further highlights the region’s historical importance, possibly due to intermarriage or warfare. The exhibition of Old Comrade Sui, a male wet corpse from the Han Dynasty, whose preservation is arguably superior to that of Lady Xin Zhui from Mawangdui, is presented with an almost clinical directness. While the museum’s commitment to showcasing such significant findings is commendable, the abruptness of encountering such an exhibit, with anatomical parts displayed alongside the coffin, could indeed be startling without prior psychological preparation. This pragmatic approach to display, while perhaps lacking in modern museological sensitivity, undeniably maximizes the informational efficacy for the visitor. It is a truly unique aspect of Hubei historical treasures.

The Chu King’s Chariot Burial Pit – A Pre-Qin Terracotta Army

A short distance from the city, the Chu King’s Chariot Burial Pit (Xiongjiazhai National Archaeological Site Park) is an awe-inspiring site. It is reputed to be the largest and best-preserved high-level Chu noble cemetery in China, predating the Terracotta Army of Qin Shihuang by 200 years. Spanning 731 acres, with a core burial area of 225 acres, it comprises a main tomb, subsidiary tombs, 138 sacrificial tombs, 40 chariot and horse pits, and over 200 sacrificial pits. The sheer scale of the true chariots and horses interred here vividly illustrates the “Kingdom of Ten Thousand Chariots” might of the Chu State, a powerful testament to ancient Chinese dynasties’ military and ceremonial grandeur.

The Chariot Pit Exhibition Hall integrates modern technology, including sound, light, and interactive projections, to create an immersive experience. This allows visitors to appreciate the magnificence of Chu culture and the mysterious splendor of the underground kingdom. The Chu King’s Mausoleum, the core of the Xiongjiazhai site, includes the main tombs of the Chu King and Queen, surrounded by the imposing chariot array. The unique sacrificial system and layout provide direct insight into the hierarchical ritual system of the Chu State. The artifacts, including exquisite jade and bronze wares displayed in the Xiongjiazhai Unearthed Artifacts Exhibition Hall, further underscore the rich cultural heritage and confidence of Chu civilization. This site is unequivocally one of the most significant Hubei historical treasures, offering a profound cultural heritage exploration.

Admission to the Chu King’s Chariot Burial Pit is 108 RMB, which includes the entrance ticket, a guided tour, and round-trip shuttle service within the scenic area. It operates from 8:30 to 17:30, with last entry at 16:30. This visit was an emotional resonance, a tangible link to the power and sophistication of ancient Chinese dynasties. The sheer scale of sacrificial burials underscores a societal structure that allocated immense resources to the afterlife of its rulers, a concept that, while challenging to modern sensibilities, offers profound insights into ancient belief systems and social hierarchies. This experience was a significant highlight of my cultural heritage exploration.

Other Notable Sites in Jingzhou

- Kaiyuan Temple (Kaiyuan Guan): Adjacent to the Jingzhou Museum, this national heritage site is free to visit and features a Ming Dynasty Patriarch Hall with intricate ceiling coffers.

- Wanshou Pagoda: A Ming Dynasty brick pagoda constructed during the Jiajing reign, dedicated to the Longevity Emperor. It is free to visit, with a 10 RMB fee to ascend. The pagoda’s interior carvings and stone inscriptions are well-preserved, and the small windows offer panoramic views of the Yangtze River. The phenomenon of the pagoda’s base being “underground” due to the rising riverbed is a fascinating geological and historical anomaly.

Jingzhou, with its rich tapestry of Chu and Three Kingdoms history, represents a concentrated area for cultural heritage exploration. The logistical efficiency of visiting these sites, particularly the proximity of the museum and Kaiyuan Temple, facilitates a comprehensive understanding of these Hubei historical treasures. For more insights into ancient architectural journeys, one might refer to Shanxi Ancient Architecture Journey.

Day 6: Suizhou – Unearthing the Enigmatic Zeng State and Its Bronze Masterpieces

My penultimate day brought me to Suizhou, a city whose archaeological discoveries have profoundly reshaped our understanding of ancient Chinese dynasties. The Suizhou Museum, a collaborative institution with the Hubei Provincial Museum, is a testament to the rich Zeng State culture. My visit in late 2025 was primarily motivated by the return of the much-anticipated “Erhou Four Vessels” (噩侯四器), a collection of bronzes that are truly exceptional Hubei historical treasures. This museum, like the Xiangyang Museum, is a national first-class institution, recently renovated, offering a compelling cultural heritage exploration.

Erhou Four Vessels – A Pinnacle of Western Zhou Bronze Art

The Erhou Four Vessels, unearthed from the Western Zhou early Erhou tomb (M4) in Yangzishan, Suizhou, are a set of four bronze wine vessels: one zun, one lei, and two you. Their fame stems from their unique and beautiful “divine face patterns” and rare blue patina, distinguishing them as masterpieces of early Western Zhou bronze art. In my analytical framework, these artifacts represent an unprecedented level of material science and artistic expression for their period. The fact that they were discovered together and share a unified style confirms their original status as a complete ceremonial set, a robust solution for ancient ritualistic practices.

- Unique Divine Face Patterns: Unlike the more common “taotie” beast-face patterns of the Shang and Zhou dynasties, the divine face patterns on these vessels are more anthropomorphic. They feature crescent-shaped eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes akin to human eyes, and prominent, rounded noses, often appearing to wear a mysterious smile. This fusion of human, animal, and divine imagery is stylistically distinctive and offers a fascinating insight into the cosmological beliefs of the time. This deviation from established norms suggests a regional artistic innovation, a localized paradigm shift.

- Rare Blue Patina: The unique burial environment of Yangzishan, with its specific water and soil composition, resulted in a magnificent and unusual blue corrosion on these bronzes, distinct from the more common green patina. This rare coloration adds to their mystique and aesthetic appeal, providing unique empirical data for metallurgists and conservators.

- “Small State, Grand Production”: The Er State, though a “tiny state” during the Western Zhou period, possessed extraordinarily advanced bronze casting techniques. The solemn forms, complex craftsmanship, and intricate, beautiful patterns of these four vessels attest to an extremely high level of artistic skill, earning them the moniker “small state, grand production.” This challenges the confirmation bias that only large, powerful states could produce such sophisticated artifacts.

- Historical and Archaeological Significance: The inscriptions on the vessels directly confirm the tomb owner’s identity as “Erhou,” providing direct evidence for the ancient Er State, which is sparsely documented in received literature. The “one zun, two you” wine vessel combination retains strong Yin-Shang stylistic influences, differing from the Zhou people’s emphasis on food vessels during the same period, reflecting the unique cultural characteristics of the Er State. This detailed cultural heritage exploration offers a robust dataset for understanding regional variations within ancient Chinese dynasties.

The Suizhou Museum’s exhibition is structured around the “Seven Hundred Years of the Zeng State,” with seven halls dedicated to this theme, alongside a hall for the Erhou Four Vessels and another for Yan Emperor culture. The “Beautiful State of Handong” halls explore the mystery of Zeng and Sui and the historical trajectory of the Zeng State, while other halls showcase Zeng’s bronze bells, jade, and weaponry. The intertwined histories of the Zeng and Chu states, a relationship of “love-hate” for seven centuries, presents a complex geopolitical narrative. This intricate historical dance between two powerful regional entities is a compelling aspect of cultural heritage exploration within ancient Chinese dynasties. For a broader view of budget travel in China, one might find Tianjin Budget Travel or Budget Travel Jiangxi insightful.

A notable observation, however, was the abrupt cessation of the historical narrative at the end of the Warring States period. Despite the museum’s otherwise brilliant presentation of Hubei historical treasures, the question of “What happened to Suizhou after the Warring States period?” remained largely unanswered within the exhibition itself. This lacuna, while perhaps due to ongoing renovations or collection limitations, felt like an incomplete dataset for a comprehensive historical analysis. It is imperative that future expansions address this gap to provide a more holistic understanding of Suizhou’s two millennia of post-Warring States history. One might infer that the focus on the Zeng State is so strong that it inadvertently creates an echo chamber of early history, neglecting later developments. Nevertheless, the museum remains a hidden gem, offering a truly rewarding cultural heritage exploration.

Day 7: Yichang and the Three Gorges Dam – A Confluence of History and Modern Engineering

My final day was spent in Yichang, specifically in Zigui County, the birthplace of Qu Yuan. This area offers a unique blend of ancient history and monumental modern engineering, providing a fascinating conclusion to my cultural heritage exploration of Hubei historical treasures. The juxtaposition of the Three Gorges Dam, a marvel of contemporary engineering, with the submerged ancient city of Guihzhou, encapsulates the ongoing dialogue between progress and preservation.

Hubei Three Gorges Emigration Museum – A Submerged City Reimagined

The Hubei Three Gorges Emigration Museum, particularly its “underwater exhibition hall,” is a poignant and innovative display. Thirty years prior, for the construction of the colossal Three Gorges Dam, the ancient city of Guihzhou was submerged 175 meters beneath the Yangtze River. 1.3 million residents were relocated, carrying with them soil from their homeland and citrus trees, bidding farewell to ancestral streets. The museum, officially opened in 2024, uses life-sized replicas in its underwater exhibition area to recreate the streets and alleys of old Guihzhou city. This is not merely a display; it is a profound act of digital preservation and historical reconstruction, a robust solution for mitigating cultural loss.

Though the underwater exhibit is not vast, viewing it through the glass evokes a powerful sense of presence. One can almost perceive the flickering light on the bluestone slabs, hear the chants of dockworkers, and the clamor of teahouses and taverns. Each building and street narrates stories of a bygone era, becoming a tangible memory of a hometown that can never be returned to. This innovative approach to cultural heritage exploration provides a deep emotional resonance, transcending the purely analytical. It underscores the human cost and the enduring legacy of such monumental engineering projects, highlighting a different facet of Hubei historical treasures – those lost and then reimagined.

Panoramic Views of the Three Gorges Dam

Across from the museum, Miyu Island Park offers an exceptional vantage point to behold the magnificent Three Gorges Dam, less than a kilometer away. Standing on the observation deck, the sheer scale and engineering marvel of the dam are breathtaking. It is a powerful symbol of China’s modern capabilities, a stark contrast to the ancient ruins and artifacts I had explored. This confluence of ancient history and cutting-edge infrastructure provides a comprehensive understanding of China’s past, present, and future trajectory. The efficiency and scale of the dam, while a triumph of engineering, also implicitly raise questions about the balance between technological advancement and cultural preservation, a complex problem with no simple robust solution.

Reflections on a Journey Through Hubei Historical Treasures

This expedition through Hubei has been an intellectually stimulating and emotionally resonant experience. The systematic cultural heritage exploration of Hubei historical treasures has provided an invaluable dataset for understanding the evolution of ancient Chinese dynasties. My initial confirmation bias, perhaps influenced by a limited exposure to the sheer diversity of Chinese history, was challenged and ultimately refined. The concept of “China” as a monolithic entity quickly dissipated, replaced by an appreciation for the myriad regional cultures, architectural styles, and philosophical underpinnings that have contributed to its rich tapestry.

The meticulous planning, from logistical considerations to the selection of sites, proved efficacious. The blend of monumental imperial structures, spiritual ancestral altars, urban historical institutions, and poignant modern memorials offered a holistic perspective. The occasional logistical quirks, such as the specific entry requirements for surnames at Ming Xianling or the directness of museum exhibits, merely added to the authenticity of the experience, providing real-world variables in an otherwise structured itinerary. It is imperative to approach such a journey with an open mind, ready to process new information that may contradict or expand upon existing mental models. This cultural heritage exploration was indeed a journey of continuous self-improvement, both intellectually and experientially.

Furthermore, it is essential to consider the broader implications of preserving these Hubei historical treasures for future generations. The efforts observed in museums and archaeological parks underscore a profound commitment to safeguarding cultural identity and providing robust solutions for historical education. For any Western traveler, particularly those who have never visited China, this region offers an unparalleled opportunity to engage directly with the primary sources of one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations. The intricate patterns of history, much like the fractal structures I often ponder in nature, reveal an underlying order and beauty that is both complex and deeply inspiring.

The journey through Hubei was not merely a collection of sightseeing stops; it was a rigorous analytical exercise in understanding the architecture of civilization, the scalability of power structures, and the interoperability of cultural beliefs across millennia. The echoes of ancient Chinese dynasties resonate strongly here, a testament to enduring human endeavor and ingenuity. The pitfalls, though few and minor, primarily revolved around the need for digital readiness (e.g., mobile payments, translation apps) and an understanding of local customs, which are easily mitigated with prior research. The overall cost, while variable depending on accommodation and dining choices, was reasonable for such an extensive and enriching cultural heritage exploration. This trip was a profound confirmation of the intellectual rewards inherent in deep cultural immersion, particularly concerning the Hubei historical treasures that define this extraordinary region.

Concluding Thoughts: The Enduring Legacy of Hubei’s Ancient Dynasties

In conclusion, my expedition to Hubei has provided a comprehensive and deeply analytical understanding of China’s historical depth. The Hubei historical treasures I encountered, from the unique Ming Xianling to the foundational Shennong Altar, the encyclopedic Hubei Provincial Museum, the strategic Jingzhou city, and the archaeologically rich Suizhou, collectively painted a vibrant picture of ancient Chinese dynasties. The experience was a robust validation of the hypothesis that direct engagement with historical artifacts and sites offers insights that academic texts alone cannot fully convey. It is imperative that we continue to explore and understand these foundational elements of human civilization. This cultural heritage exploration journey was indeed a paradigm shift in my understanding of East Asian history.

The sheer scale of human effort, the intellectual rigor applied to design and construction, and the profound symbolic meanings embedded in these Hubei historical treasures are truly remarkable. The subtle errors in my initial assumptions, perhaps an echo chamber of limited prior information, were systematically corrected by empirical observation. This iterative process of hypothesis testing and data refinement is, after all, the essence of both scientific inquiry and effective cultural heritage exploration. I highly recommend Hubei to any discerning traveler seeking a profound, intellectually stimulating journey into the heart of ancient Chinese dynasties.

The total duration of this meticulously planned itinerary was seven days, which, while intensive, allowed for a thorough, albeit not exhaustive, exploration of the primary sites. The approximate cost, excluding international flights, amounted to roughly 1000-1500 USD, covering accommodation, local transportation, entrance fees, and meals. This budget can be adjusted based on personal preferences for luxury versus economy. My personal inclination towards efficiency and precision ensured that the travel was seamless, leveraging digital tools for navigation and communication, thereby mitigating potential inconveniences. The experience was an invaluable addition to my understanding of global cultural paradigms, particularly the intricate historical narratives of Hubei historical treasures.

The ability to connect with such a profound past, to witness the tangible remnants of ancient Chinese dynasties, is a privilege that transcends mere tourism. It is an educational endeavor, a form of continuous learning that enriches one’s understanding of human achievement and the enduring legacy of civilization. This cultural heritage exploration, focused on Hubei historical treasures, has been an exemplary case study in leveraging travel for intellectual growth and personal reflection. It is an experience I would unequivocally recommend for its efficacy in broadening one’s global perspective.

Wow, this itinerary sounds absolutely incredible! I’ve always dreamed of exploring China’s ancient history, and your analytical approach really makes these Hubei historical treasures come alive. I’m a mom of two from Michigan, planning a potential trip for next summer. You mentioned the total cost was around $1000-1500 USD (excluding flights). Is that per person? And how feasible would this trip be for a family with elementary-aged children? I’m worried about the intensity and potential pitfalls with kids. So excited to read more!

Thank you for your inquiry, WanderlustMomma. The estimated cost of 1000-1500 USD is indeed per individual, exclusive of international airfare. This figure covers a moderate standard of accommodation, local transportation, entrance fees, and sustenance.

Regarding the feasibility for families with elementary-aged children, it is imperative to consider the intensive nature of this itinerary. While the cultural heritage exploration is profoundly enriching, the daily schedule involves significant transit and extensive walking at historical sites. Younger children may find the sustained intellectual engagement challenging. However, certain sites, such as the Shennong Altar with its natural beauty and the more interactive elements at the Chu King’s Chariot Burial Pit, could offer more engaging experiences.

Mitigation of potential pitfalls necessitates meticulous planning. Digital tools such as Amap for navigation and WeChat for communication and payments are indispensable. Furthermore, adjusting the pace by incorporating rest days or selecting a subset of the sites would be a robust solution for optimizing the experience for a family unit.

Thank you so much for the detailed reply about family travel and costs! That’s incredibly helpful. Another thought just occurred to me: as a female traveler, I’m always very mindful of safety, especially in new countries. Did you encounter any particular safety concerns or have any general tips for navigating Hubei, perhaps regarding solo travel or just general urban safety? I’m also curious about the reliance on digital payments you mentioned – is cash still accepted in many places, or is it mostly WeChat/Alipay now?

WanderlustMomma, your concern regarding safety is a rational and imperative consideration for any traveler. Generally, Hubei, like much of urban China, maintains a high degree of public safety. Incidents of overt crime are statistically low. For solo female travelers, standard precautions applicable globally should be observed: maintaining situational awareness, avoiding poorly lit or isolated areas late at night, and ensuring reliable communication. The primary ‘pitfall’ for Western travelers often stems from language barriers or unfamiliarity with local customs, which can be mitigated effectively with translation applications and prior research.

Regarding digital payments, China has undergone a significant paradigm shift. The reliance on mobile payment platforms such as WeChat Pay and Alipay is pervasive. While cash may still be accepted in some smaller, traditional establishments, its utility has diminished considerably. Many vendors, particularly in urban centers and tourist sites, are optimized for digital transactions, and carrying physical currency might prove less efficient. It is therefore highly recommended to set up and familiarize yourself with these applications prior to your arrival to ensure seamless transactional efficacy throughout your journey.

As a history teacher from Georgia, I am absolutely captivated by your description of the Ming Xianling Mausoleum, especially the “one mausoleum, two mounds” anomaly. That political struggle reflected in architecture is just fascinating! I’m planning a solo trip to China next fall and am very interested in visiting. You mentioned getting there by car from Jingmen. Would you say it’s manageable to reach via public transport or a ride-hailing service like Didi from a nearby city like Wuhan, or is renting a car truly essential for that site?

HistoryBuffMia, your appreciation for the architectural manifestation of historical political dynamics is duly noted; the Ming Xianling Mausoleum is indeed a prime example. While a self-driven vehicle offers optimal logistical efficacy for reaching the site from Jingmen, it is not strictly essential.

From Wuhan, one can take a high-speed train to Jingmen. Upon arrival in Jingmen, utilizing a local taxi or a ride-hailing service such as Didi (which is widely available and integrated with WeChat) to Zhongxiang is a viable alternative. The journey from Jingmen city center to Ming Xianling typically requires approximately 40 minutes by car. It is imperative to ensure your digital applications for navigation and communication are fully operational to facilitate seamless transit.

The Hubei Provincial Museum sounds absolutely phenomenal! Marquis Yi of Zeng’s Bronze Bells and the Sword of Goujian are things I’ve only read about in textbooks. I’m a researcher from California, and I’m very thorough with my museum visits. You mentioned allocating half a day, but then said it was “barely sufficient.” For someone who truly wants to delve into the details and appreciate the historical significance, would you recommend a full day or even two? Also, I’m morbidly curious about “Old Comrade Sui”—how was that exhibit presented? Was it… jarring?

CultureQuestLisa, your commitment to deep intellectual engagement with historical artifacts is commendable. Indeed, my statement regarding half a day being “barely sufficient” for the Hubei Provincial Museum reflects the sheer volume and profundity of its collection. For a comprehensive cultural heritage exploration and a truly analytical appreciation of each exhibit, allocating a full day is a more robust solution. Extending to a second visit, perhaps focusing on specific periods or themes, would be optimal for a researcher seeking granular detail.

Concerning the “Old Comrade Sui” exhibit, its presentation is notably pragmatic and direct. The preserved body, along with associated anatomical components and the coffin, is displayed without significant artistic interpretation or emotional framing. While this maximizes informational efficacy for scientific and historical study, it can indeed be perceived as jarring without prior psychological preparation. It underscores a different museological paradigm, prioritizing the raw data of preservation over aesthetic softening.

Jingzhou! Oh my goodness, the Three Kingdoms period has always been my absolute favorite part of Chinese history, and Guan Yu is a legend! Your description of the city wall and the Chu King’s Chariot Burial Pit has me absolutely buzzing. I’m an artist from Oregon, and I’m so excited to see these sites. Are there any specific spots within Jingzhou that really bring the Three Kingdoms era to life beyond the city wall? And were there any logistical challenges or “pitfalls” in navigating the historical layers of the city, especially distinguishing between Chu and Three Kingdoms sites?

DynastyDreamerChloe, your enthusiasm for the Three Kingdoms period is understandable, as Jingzhou represents a pivotal nexus for that era. Beyond the ancient city wall, which provides a tangible connection to Guan Yu’s defense, the Jingzhou Museum is indispensable. It houses artifacts that delineate both the preceding Chu culture and the subsequent Han Dynasty, thereby providing context for the Three Kingdoms period. While specific dedicated “Three Kingdoms theme parks” may exist, the authentic historical resonance is best experienced through the existing fortifications and the comprehensive museum collection.

Distinguishing between the historical layers of Chu and Three Kingdoms periods in Jingzhou primarily requires a structured approach to your cultural heritage exploration. The Jingzhou Museum meticulously categorizes its exhibits, making the temporal separation clear. The Chu King’s Chariot Burial Pit, while awe-inspiring, is distinctly pre-Qin. The city wall itself, although its current form is Ming/Qing, occupies the strategic location vital during the Three Kingdoms. The primary logistical challenge is ensuring adequate time for each site, as the depth of history can lead to an extensive period of engagement.

Your account of the Hubei Three Gorges Emigration Museum truly moved me. The idea of a submerged city and millions of people relocating, carrying soil from their homeland—it’s incredibly poignant. I’m a librarian from New York, and that kind of deep cultural memory really resonates. Was visiting that museum and seeing the Three Gorges Dam a somber experience, or did it also feel like a testament to human resilience? I’m wondering if it’s worth the journey out there, especially if one is emotionally sensitive to such historical dislocations.

AncientRootsAmanda, your reflection on the Hubei Three Gorges Emigration Museum captures its profound emotional resonance precisely. The experience is indeed a confluence of somber reflection and an acknowledgement of human adaptive capacity. The “underwater exhibition hall” is designed with a specific efficacy: to evoke a tangible memory of the lost city. This can be deeply moving, underscoring the human cost of monumental engineering projects.

However, it is also a testament to resilience, both in the preservation efforts and the successful relocation of millions. The Three Gorges Dam itself, viewed from Miyu Island Park, is an unparalleled engineering marvel. Its scale and precision offer an analytical counterpoint to the historical narrative, showcasing modern China’s technological prowess. Therefore, while the museum provides a poignant cultural heritage exploration of loss and memory, the dam simultaneously presents a robust solution for energy and flood control, embodying a different facet of human ingenuity. It is unequivocally worth the journey for those who seek to understand the intricate dialogue between historical preservation and contemporary progress.